How Our Brain Learns and Adapts: The Magic of Memory Reconsolidation

Understanding how our brains learn, adapt, and change through memory reconsolidation not only gives us insight into our own behaviors but also opens up new possibilities for personal growth and therapeutic techniques. Whether we’re dealing with past traumas or looking to improve our adaptive strategies, the dynamic nature of memory offers hope for lasting change.

When we’re born, our brains aren’t fully developed; they’re like houses with just the framing up. So, in the beginning, we heavily rely on our lower brain areas and start interacting with the world through our core emotions. These primal interactions happen through instinctive reactions to our sensory experiences. The feedback from these experiences gets stored and helps us learn. Over time, with repetition, these experiences turn into long-term, non-declarative memories, creating implicit prediction models (see our easy to read post on implicit prediction models).

Our brains learn through a method called prediction error. If a prediction is wrong, we update it; if it’s right, we stick with it. This process, which Freud called the Reality Principle, helps us use energy efficiently while adapting to survive. Memories and predictions guide our actions, from our posture to social strategies and facial expressions. These non-declarative memories are (like Tinactin) quick-acting and long-lasting, making them reliable for forming automated prediction models, even though updating them can be tough.

However, these memories can be updated through a process called memory reconsolidation. When we recall and viscerally feel these implicit memories, they become destabilized and open to new information before consolidating again. The provides a potential to change deeply held connections between emotions, events, and self-protective behaviors if new, powerful experiences contradict old expectations. Thus, memory is a constructive process, piecing together bits of the past to predict the future. We are still learning how and where this can apply clinically but any good effective psychotherapy will harness this mechanism in the brain.

Our subcortical systems, memories, and prediction models support the brain’s higher functions, like thinking and feeling. The cortex, allows us to learn and adapt. Unlike our primary instincts, learning involves creating predictions about what is adaptive at the moment (instincts are built in, we don’t have to learn them). What we learn as adaptive may therefore differ from instinctive reactions.

Memory Reconsolidation: A Deeper Dive

Karin Nader and Oliver Hardt’s groundbreaking work revolutionized our understanding of memory. Before their research, it was believed that memories formed linearly, transitioning from short-term in the hippocampus to long-term storage elsewhere. They showed that recalling long-term memories makes them unstable and requires reconsolidation to remain long-term. This means memories can change each time they're recalled, making memory a dynamic process.

Their research indicates that after a memory is reactivated, it stays open to new learning for about six hours before reconsolidating. This process doesn’t damage the brain and is specific to individual memories. Memory reconsolidation has since influenced psychotherapy, such as Bruce Ecker’s Coherence Therapy, by showing that old memories can be updated with new emotional experiences, facilitating growth and reducing anxiety.

This concept aligns with Frank Alexander’s idea of the corrective emotional experience, suggesting that updating old memories with new, positive experiences can help resolve long-standing emotional issues. Interestingly, Nader and Hardt were students of neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux, who initially doubted their hypothesis but changed his stance after they proved it correct.

Understanding how our brains learn, adapt, and change through memory reconsolidation not only gives us insight into our own behaviors but also opens up new possibilities for personal growth and therapeutic techniques. Whether we’re dealing with past traumas or looking to improve our adaptive strategies, the dynamic nature of memory offers hope for lasting change.

Example of Implicit Prediction Models: Riding a Bicycle

Go beyond TikTok mental health. If you want to understand and change your mental health start with this important concept. Then check out the post on memory reconsolidation to see the application.

Implicit prediction models is an important concept to understand in order to understand mental health. When you first learn to ride a bike, it's a challenging process that involves a lot of trial and error. Here's how implicit prediction models play a role:

Initial Experience:

The first time you get on a bike, your brain has no experience or model to predict how to balance, pedal, and steer simultaneously.

You rely on basic instincts and sensory feedback. You might wobble and fall several times.

Feedback and Learning:

Each time you fall, your brain gets feedback about what didn’t work.

When you manage to ride a few feet without falling, your brain receives positive feedback, noting what you did correctly.

Formation of Implicit Prediction Models:

Over time, with repeated practice, your brain starts to form implicit prediction models. These are automatic, unconscious processes that predict how to balance, steer, and pedal based on past experiences.

These models help you make tiny adjustments to your balance and movements without consciously thinking about them.

Consolidation into Long-Term Memory:

As you continue to practice, these experiences consolidate into long-term, non-declarative memories.

Eventually, you can ride a bike smoothly without consciously thinking about balancing or steering. Your implicit prediction models handle these tasks automatically.

Automatic Adjustments:

When you encounter different terrains, like going uphill or downhill, your implicit prediction models adjust your body’s movements to maintain balance.

You don’t have to relearn how to ride every time; your brain uses the prediction models to adapt quickly.

This process shows how implicit prediction models allow us to perform complex tasks automatically, freeing up our conscious mind to focus on other things. It’s these models that make activities like riding a bike feel second nature after enough practice.

The basic problem that brings people to therapy: Part One

I would wager that most of what brings people to therapy are emotional conflicts. Emotional conflicts are the results of some kind of trauma experience. When emotional conflicts come from growing up they are considered symbols of what’s called, developmental trauma (sometimes called “small ’t’ trauma”). When they are in connection to a shocking or harrowing moment or event they are considered symbols of what’s called, shock trauma (sometimes called “large ’T’ trauma”).

Emotional Conflicts, defenses and the dynamic unconscious

I would wager that most of what brings people to therapy are emotional conflicts. Emotional conflicts are the results of some kind of trauma experience. When emotional conflicts come from growing up they are considered symbols of what’s called, developmental trauma (sometimes called “small ’t’ trauma”). When they are in connection to a shocking or harrowing moment or event they are considered symbols of what’s called, shock trauma (sometimes called “large ’T’ trauma”).

Here’s what I mean, at some point we have an emotion or set of emotions and are in need but when we express them or try to express them it doesn’t go well. Maybe they get us nothing of support, maybe they get us criticized or attacked maybe they get us ignored. When this happens the first thing we’ll feel is panic. If our panic response doesn’t result in people re-adjusting and supporting us then we feel helpless and alone (and still in need). Any of those ill tuned responses likely will also cause us to feel shame on top of the unrelieved stress we are already feeling. If that happens strong enough (i.e. shock trauma) or enough times (i.e. the “death by a thousand paper cuts” of developmental trauma) we remember it and adjust in the future. So we learn to feel alarmed when those emotions happen again because we fear getting hurt again and we also learn to automatically feel bad about ourselves when those feelings happen, as if there is something wrong with us (i.e. we re-experience the shame that we felt then). That is an emotional conflict.

Coping with emotional conflict

So how does our body and mind deal with emotional conflict? Well, we can’t control what we feel but we can protect ourselves from feelings we fear get us hurt. We do this by using something called dissociation. This is basically a way to distract ourselves and not know what we’re feeling. Another word for these distractions or dissociation is defenses.

Defenses

Defenses can be internal or external or both. When they are internal they involve a distortion of reality. We may feel that everything is our fault, or someone else’s fault, we may attribute our emotions to someone else (e.g. “I’m not angry, you’re angry”), we may feel paranoid, we may feel very helpless and just retreat and hide (this could include going numb emotionally), we may feel like someone or the situation is all good or all bad, we may under weigh the severity of the situation or over weight it, etc. External distractions may be the use of substances, shopping, eating, exercising, work, sex, creating drama, and of course the ever present phone in our pocket beckoning us to scroll just a little more, etc. Defenses correlate to what age we were when we first had to cope with this emotional conflict. Diagnostically, this is helpful because certain defenses can give clues to when a trauma may have happened in the lifespan. Think of it this way, if you are a baby you only have so many ways to protect yourself, you are pretty helpless, so things like denial of reality, rage, or extreme withdrawal or closing your eyes and hiding somehow are kind of the best you can do. Additionally, if you take on intense shame as a baby it really hinders your ability to grow healthy self esteem (e.g. you might develop a more fragile sense of self and be prone to addiction, deep humiliation and/or fits of rage when you feel too vulnerable). Likewise, if you experience something later in life you have more tools available to cope (both with the stress and the shame). For example, you might learn to tell jokes instead of feeling the emotions.

Summary

Basically, when you experience an emotional suffering you can’t solve you have to cope somehow to survive. That coping distracts you from the real needs you feel. In this way coping doesn’t really solve the issue but it does help you get through it. When that happens it’s that coping that gets recorded and remembered in the body and mind. So the next time you feel that way it is the coping that is used to get through it again (even if you’re not really in the same situation again). This becomes habit and eventually automatic and, over time, part of your personality. Another way to talk about things that are automatic (like defenses or coping) is that they are unconscious. So, defenses are automatic or unconscious. We don’t know when they are occurring. This is worth repeating. We don’t know when they are occurring. Our view of reality slips from in tune to a distortion based on past pains in the blink of an eye. We still think we are seeing clearly when we are actually seeing the past. No matter the current reality we see threat. This protects us from feeling the vulnerable emotions evoked that are marked as threatening because originally when we had those feelings we got hurt. This is the point of defenses, they help our system feel calm when we are experiencing upsetting emotions that we don’t know how to solve for.

Navigating Conflict Beyond Trigger Warnings

Conflict is challenging. It becomes even more difficult when a trauma response is triggered. Imagine treating a minor issue like a major crisis—a "five-dollar problem" escalating to a "five-hundred-dollar problem." This often happens unconsciously, making it feel like a rational reaction. So, how can we address a problem that we can't directly perceive? Here are three steps to help navigate this issue:

Conflict is challenging. It becomes even more difficult when a trauma response is triggered. Imagine treating a minor issue like a major crisis—a "five-dollar problem" escalating to a "five-hundred-dollar problem." This often happens unconsciously, making it feel like a rational reaction. So, how can we address a problem that we can't directly perceive? Here are three steps to help navigate this issue:

Awareness

Trauma responses encompass physical, mental, emotional, and visceral layers. Although these responses are typically unconscious, we can bring them into our awareness. Increasing awareness reduces dissociation, allowing us to detect our feelings, thoughts, actions, and sensations when triggered. To practice this, think about a situation where past pain caused you to overreact in the present. Stay grounded in the present while asking yourself:

What do I think when I'm triggered?

What do I feel emotionally when I'm triggered?

What do I do (both verbally and physically) when I'm triggered?

What do I sense viscerally when I'm triggered?

Slow Down

Slowing down involves observing without acting. Notice your answers to the above questions, but resist the urge to act on them. This practice, known as mindfulness, creates a gap between your reaction and your actions. To activate your parasympathetic nervous system (the calming "brake pedal"), try the following techniques:

Take a physiological sigh (two breaths in, one breath out)

Drink some water

Spend time in nature or with a beloved pet

Practice orienting (check out our video on this technique)

Reflective listening (repeat back what the other person said until they confirm you understood correctly)

Reflect

Reflection involves thinking about your thoughts, feelings, sensations, and desires. Assess whether your desires align with the situation and your values. Often, you'll need to find a compromise between your immediate impulses and your core values to achieve a beneficial outcome.

Decide and Act

Once you've reflected, consciously decide on the best course of action. Now, you're ready to address the situation appropriately, treating a five-dollar problem like a five-dollar problem.

By following these steps, you can navigate conflicts more effectively, reducing the impact of unconscious trauma responses and fostering healthier interactions.

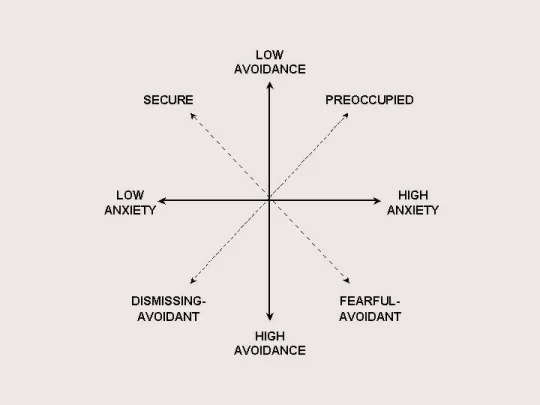

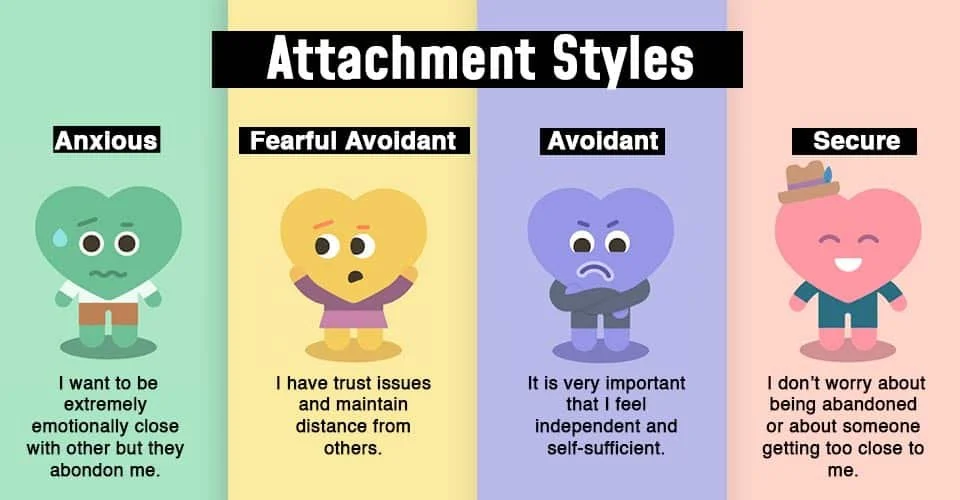

What Are Attachment Styles?

Attachment styles are ways people connect and relate to others based on their early experiences with caregivers…These patterns often continue into adulthood and influence romantic relationships. People tend to form relationships with partners who have similar attachment styles to one or both of their parents.

Attachment styles are ways people connect and relate to others based on their early experiences with caregivers. John Bowlby, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, developed Attachment Theory, sometimes called the science of love, after studying relationships between mothers and troubled teenagers. He wanted to understand how early relationships influenced later behavior. Along with his colleague Mary Ainsworth, who studied interactions between parents and young children, they identified different attachment styles based on how children responded to connection, separation, and reconnection with their caregivers.

Ainsworth's research led to the creation of "The Strange Situation," a study that helped categorize four main attachment styles.* These styles are learned behaviors developed in response to early experiences of distress and are not meant to label someone as good or bad. Instead, they show how a child felt they needed to behave to feel emotionally safe with their caregiver. These unconscious patterns often continue into adulthood and influence romantic relationships, parenting, friendships and professional life. People tend to form relationships with bosses, co-workers, friends and partners who have similar attachment styles to one or both of their parents.

The Four Attachment Styles

1. Secure Attachment

Children with secure attachment felt listened to and trusted that their feelings would be respected. They grow up with a healthy ability to handle emotions and feel good about themselves.

2. Anxious/Ambivalent (Preoccupied) Attachment

These children experienced inconsistent attention from their parents, leading to prolonged anxiety. They learned to keep their parents' attention by being pleasing or entertaining, but this created a sense of low trust and a need to control. As adults, they might seem clingy, angry, controlling, or critical, stemming from a deep fear of abandonment and insecurity. Often they have to dissociate negative emotions like anger for fear it would cost them the relationship.

3. Dismissive/Avoidant Attachment

Children with this attachment style learned that expressing big emotions would be ignored, so they turned down their anxiety and disconnected from their feelings. They often come off as self-sufficient, preferring solo activities over team or emotional ones. They might appear uninterested in close relationships, masking low self-esteem with an inflated sense of independence.

4. Anxious/Avoidant (Fearful Avoidant) Attachment

These children experienced both pain and comfort from their parents, often due to abusive relationships. They couldn't develop a stable coping strategy, leading to a mix of needy and avoidant behaviors. This "come here/get away" approach causes high anxiety and difficulty regulating emotions, resulting in low self-esteem and low trust in others.

Understanding Attachment Styles

Attachment styles are patterns of feeling, thinking, and behaving around emotions and conflict. They can change over time with effort and can vary with different caregivers. Recognizing your attachment style can help you understand your behaviors in relationships and work towards healthier connections.

I like this free Attachment Style assessment outside of an officially administrated test: https://www.attachmentproject.com/blog/four-attachment-styles/

*There are good critics that these initial assessments were not done with a broad enough sample size. There have been many follow up studies to work to validate the categories across cultures. However, I think it is still a working theory (as most things are) and worth holding in tension with diverse norms. People want to grab these studies and use them to dictate health/unhealthy and I think that can be tricky at best and dangerous at worst. I find this especially happens when religion or morals are superimposed onto them.

What Counseling Isn’t: Clearing Up Common Misunderstandings

It might seem odd to write about what counseling isn’t, but there's a lot of confusion about effective therapy. So, let’s clear up some misconceptions.

It might seem odd to write about what counseling isn’t, but there's a lot of confusion about effective therapy. So, let’s clear up some misconceptions.

Counseling is Not Giving Advice

A friend once mentioned they were unsure if their loved one’s therapist was giving good advice. This is a common misunderstanding. People often think therapy is about being told what to do. But, imagine a therapist as an archeologist. They dig in areas where they believe they might find significant artifacts. When they find something, they carefully uncover and study it to understand the bigger picture.

Similarly, therapists help you explore your thoughts, feelings, sensations, and memories. They work with you to understand these elements and how they fit into the bigger picture of your life, often uncovering connections to past traumas. The goal isn’t to give advice, but to help you understand yourself better and develop strategies to create meaningful change in your life.

Counseling is Not Quick or Easy

Many people are surprised by how long therapy can take, as well as the time, effort, and cost involved. Changing your brain and breaking old habits is a delicate, slow process. While there are aids like medication or alternative methods that can support therapy, the core work is often gradual and requires patience.

Counseling is Not a Regular Conversation or Relationship

Therapy conversations are unique. They aim to access parts of you that don't typically come up in everyday interactions. This means the topics and the way you talk about them are different. You might be encouraged to express your true feelings, which can be challenging and make you feel vulnerable. Therapists aren’t interested in being politically correct or sticking to societal norms—they focus on what truly is. There’s no right or wrong, just what exists.

Moreover, the therapist-client relationship is different from a regular friendship. It’s a unique bond with emotional intimacy, where the therapist knows a lot about you, but you know less about them. This imbalance, however, creates a powerful connection essential for making progress. You might feel younger, more empowered, or different in other ways compared to your daily relationships. As trust builds, you’ll become more open to feelings you’ve previously hidden, allowing them to surface and be addressed, whether they stem from developmental stages or trauma.

Understanding these distinctions helps in appreciating what therapy is truly about: a journey of self-discovery, healing, and growth, rather than a quick fix or a series of friendly chats.

What does a first session look like at analog?

What does a first session of therapy look like? Glad you asked.

Once you’ve been met in the waiting area you’ll be guided back to our office. There you’ll find two chairs and a loveseat. We don’t have a special chair. One of the first parts of therapy actually happens in choosing where to sit. Not because we’re analyzing what does your choice mean but because we are encouraging you to engage your sense of agency and boundaries. We look to you and your nervous system to identify which space feels most comfortable to you. Additionally, we look to see where your nervous system feels best about where we sit as the threrapist. We might ask you if this feels okay for us to sit here. We are hoping you will track yourself and really speak your opinion. We might ask you how you know it feels okay. We are looking for you to check in with your viscera and sense whether you feel uncomfortable or at ease. There are no secret readings of the moment, you are the one who supplies us with the information.

After sitting down we’ll go over the paperwork you have already read and signed digitally. We’ll highlight key features like HIPAA, office policies, and how therapy works with us.

Then you’ll be invited to let us know what brings you to therapy. You can say as much or as little as feels right to you.

While we listen we will also be tracking your non-verbals, looking for cues of stress or trauma or places of activation (repetitive motions, shaking legs, wincing, pulling body or face away suddenly, etc.). Again, this is not to gain secret knowledge of you, if we notice something we’ll bring it up and wonder about it with you. You’ll be the one to determine whether it feels meaningful to that moment or not.

We might learn a couple of techniques like orienting, and SIBAM tracking (tools you’ll use throughout the therapy and beyond) and the therapist will work to give you a summary of what you’ve said and identify what a course of therapy might look like based on what you’re experiencing.

Finally, scheduling and frequency are determined together.

Payment is normally done by the clinician later on using the card you’ve put on file. Of course if you prefer other types of payment then that is used instead.

So there you go, a simple overview of a first appointment! The main thing we want to emphasize is that you aren’t being judged or secretly analyzed or read. We are collaborative and start with a paradigm of seeing you as a good person and seeing emotional struggles not signs of corruptness or flaws but as normal ways the body and mind work to cope.

The Hidden Impact of Unresolved Fight, Flight, or Freeze Responses

When our natural threat response cycle is interrupted, it can easily be mistaken for other issues. By understanding the threat response cycle that all mammals experience, we can gain better insight into our reactions and overall mental health.

What is the Threat Response Cycle?

Imagine you're out for a walk and you hear a twig snap, or you see an unexpected movement out of the corner of your eye. Maybe you’re at work and you get an alert for an impromptu meeting, etc. These instances kick off a process known as the threat response cycle:

Notice Something New: This could be any sudden change in your environment—sounds, smells, sights, or even digital notifications.

Orient to the Novelty: Your attention shifts to this new stimulus.

Assess for Danger: Instinctively and automatically, your brain evaluates whether this new thing poses a threat.

Activate Response: If it’s deemed dangerous (this is not a conscious decision), your body kicks into one of the three F’s: fight, flight, or freeze.

Return to Normal: If it’s not a threat (like realizing that "snake" is actually just a garden hose), your body relaxes, and you return to your normal state.

But what happens if your response to a threat gets interrupted? Say, you feel intense anger but can't express it, or you're scared but can’t escape. If your fight, flight, or freeze response isn’t completed, that energy gets stuck in your system.

Why Does This Matter?

Unresolved fight, flight, or freeze responses can cause various issues. They might be mistaken for problems with self-control, personality flaws, or even physical ailments. For instance, feeling inexplicably anxious or irritable could be the result of a stuck fight or flight response, not a personal failing.

Understanding this cycle is crucial for mental health. It helps us recognize that these reactions are natural and part of our biology. Completing these responses, even if it's after the fact through therapeutic practices, can help us return to a state of balance. Somatic Experiencing is an effective way to do this.

Final Thoughts

Recognizing and addressing stuck fight, flight, or freeze responses is essential for mental and physical well-being. By understanding this natural cycle, we can better navigate our reactions to stress and create more room for healing and growth. If you think unresolved responses might be affecting you, talking to a counselor can be a great step toward resolving these issues and finding peace.

Rethinking Mental Health: Embracing the "Choose Your Own Adventure" Metaphor

In my last post, I touched on how viewing mental health through a strict medical lens can hold back progress. The medical model labels things as healthy or unhealthy, good or bad, and this binary thinking just doesn’t fit when it comes to mental health. (And yes, even the term "mental health" has its issues, but let’s tackle one thing at a time.) Today, I want to introduce a different metaphor: think of mental health as a "choose your own adventure" story.

Everything Tells a Story

Everything we do, feel, and think carries meaning. It might be a small detail or something significant, but it all contributes to the story we're living. It can be exhausting to stay on top of everything, and it’s tempting to dismiss some things as meaningless. But here’s the good news: we’re not trying to write a story or determine its meaning; we’re here to listen to the story being told.

The words we use, the tension in our muscles, the way we look or avoid looking, the emotions we feel or suppress, the intensity of those emotions, our behaviors, our thoughts, our levels of engagement—they all tell a story. Often, the real story isn’t just what's on the surface. In therapy, we’re trained to listen to everything, not just the spoken narrative. We call this "process vs. content." For example, you might say one thing, but your hand gestures might reveal something different.

Moving Beyond the Medical Model

Using the medical model can increase the risk of shame. Why? Because getting curious about something can trigger a fear that we’ll find something "faulty" or "unhealthy." But if we approach it like a psychotherapy model—where we listen for the story without judgment and assume everything that surfaces is normal given the context—there is no right or wrong. This frees us to remain curious and keep listening.

In Somatic Experiencing work, this might lead to noticing imagery, movements, or sensations. In psychotherapy, it might bring greater insight and clarity.

The Therapist as a Curious Companion

This isn’t a “gotcha” approach. The therapist isn’t an expert who sees what you can’t. They are a curious companion who might notice something and wonder about it with you. By listening to the story your body-mind is telling, without trying to force it into a specific framework, we can follow the adventure your system chooses. This is what ultimately leads to feeling better.

So, let’s ditch the rigid medical model and embrace the idea that mental health is like a choose your own adventure story. By listening to our stories and staying curious, we open up the path to genuine understanding and healing.

Two Common Misconceptions About Mental Health and How to Overcome Them

Hey there! Let's talk about two common misconceptions about mental health that can really get in the way of making real progress:

Misconception 1: Treating Symptoms Instead of the Root Cause

We often mistake the symptoms of mental health issues for the problem itself. So, we end up trying to manage these symptoms—like negative thoughts, anxiety, or depression—instead of digging deeper to understand what they actually represent. For example, these symptoms might be rooted in traumatic memories that have shaped how we respond to situations in the present. If we only focus on managing the symptoms, we're not addressing the underlying issues that cause them.

Misconception 2: Using Medical Metaphors for Mental Health

Another big misunderstanding comes from how we talk about mental health. You’ve probably heard people say, "I have anxiety" or "I have depression," like it’s something they’ve caught, similar to "I have a cold" or "I have a broken bone." This medical language implies that these mental states are static and abnormal, but that’s not really the case. Anxiety and depression are important and natural states that everyone experiences to some extent, and they fluctuate over time.

Even chronic states of suffering often indicate that the nervous system is responding exactly as it should, based on past trauma. The system is on high alert or shut down because it's unconsciously using old, trauma-based information to navigate current situations, which might not be helpful unless that same historical trauma is happening again.

The Bigger Picture

Of course, mental health is complex, and there are exceptions to these ideas. But generally speaking, shifting our focus from just managing symptoms to understanding and addressing their root causes, and rethinking how we conceptualize mental health, can make a big difference in our approach to healing and change.